Cyprus House

21 March 2024

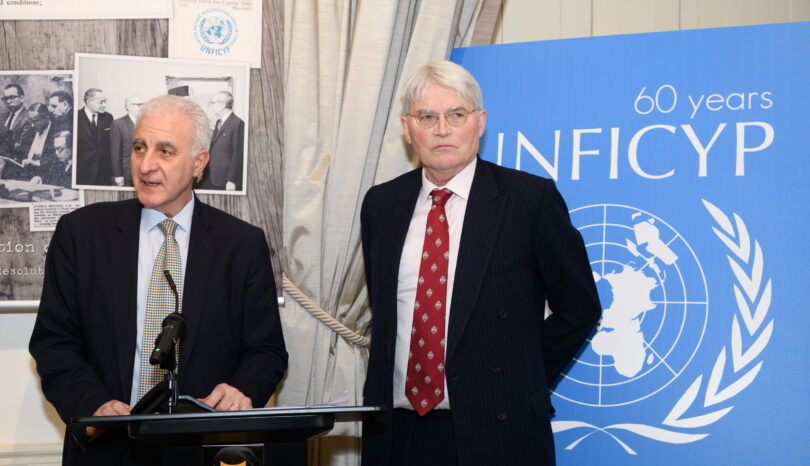

Minister of State, the Earl of Minto,

Excellencies,

Colleagues,

Distinguished guests,

And most of all veterans of UNFICYP,

It is with great pleasure that I warmly welcome you all to Cyprus House. I particularly want to welcome and acknowledge the many veterans of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus, commonly known as UNFICYP. You are the reason we are gathered here today. This month, marks 60 years since the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 186 (1964), under which the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus was established. Today’s event is held to pay tribute to those British military personnel who have served in UNFICYP, to thank them for their service and for their support in Cyprus’ quest for peace over the last six decades. There are veterans in this room who served in 1964 and others who served as recently as in 2020.

According to United Nations sources, more than 150,000 troops have served in UNFICYP since its establishment, with 6300 arriving on the island by the end of 1964. Forty-three countries contributed troops to the Force. I am pleased to see many of those countries are represented here today and I thank them for joining us and for their countries’ contribution to UNFICYP. The United Kingdom, has been one of the largest troop contributors throughout UNFICYP’s existence. The British contingent is now stationed at Ledra Palace in Nicosia and is responsible for Sector Two, as it is called, patrolling and monitoring military activity in 30km of the buffer zone, part of which runs through the capital Nicosia. Today UNFICYP numbers about 850 troops with 257 of its personnel coming from the UK.

In March 1964, the UN Security Council answered the request of the Cypriot Government to assist it, in re-establishing order on the island, following intercommunal clashes, with the adoption of Resolution 186. Apart from the goal of contributing to the restoration of law and order, prevent the recurrence of fighting, and to contribute to a return to normal conditions, the Security Council was also cognisant of the need to prevent the localised violence from spreading into a wider conflict between two of the guarantor powers, Greece and Turkey.

In December 1963 the Government of this young Republic, only three years after gaining its independence, having been a British colony was trying to find its way through a constitutional crisis. In its effort to gain control of the situation immediately, so, before the blue berets arrived by mid-March 1964, the Cypriot Government had invited the three guarantor powers to assist it in securing a ceasefire and restoring law and order. The joint force that was formed became operational upon the agreement of President Makarios, Vice President Kuchuk and the governments of the United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey. It is extraordinary to have with us today, veterans who served in that first “Truce Force” as it was called, which was British-led, under the command of General Peter Young. You will all have heard of the buffer zone in the centre of Nicosia often called “the Green line”. The phrase is attributed to General Young, who used a green wax-pencil to draw the area to be patrolled by the joint force to sustain a ceasefire between the two communities. Unbeknownst to him, ten years later, that same line would become a 180 kilometers, extending, from west to east, a line that continues to this day and which separates the Cypriot population across the island.

Peacekeeping operations in the late 60s and early 70s were different to the late 70s and beyond. This reflected the task at hand when the Force was established. Tensions were localised within areas, identified as Districts. As most of you know from having served there, the British contingent at the time was deployed in the Limassol District. In the immediate years that followed the 1963/64 intercommunal strife, UNFICYP maintained a “delicate equilibrium” between the two communities by non-forceful means, as it was reported from the ground by the early 70s. Negotiations between the communities were ongoing and at times looked hopeful that a settlement could be reached. The numbers of the Force diminished to just over 3000 by 1972 and more tasks were transferred to UNCIVPOL, the civilian police arm of the UN’s presence on the island.

Conditions critically changed on July 20th, 1974 with Turkey’s invasion, following the coup instigated by the then military junta in Greece five days earlier. UNFICYP was neither equipped, nor prepared, nor mandated to confront or halt the Turkish armed forces. In the face of this overwhelming, full force invasion, with aerial and naval bombardments followed by troop landings, there was no strategy or operational plan from UN Headquarters. In fact, Sir Brian Urquhart, the Under-Secretary General for Political Affairs at the time explains later in his written work that the only thing the UN Secretary General could ask the Commander of the Force, Prem Chand of India, to do was “to play it by ear”. As “Operation Attila”, as it was called, unfolded, UNFICYP often came under threat from the Turkish army, demanding that the UN withdraws from the locations it was targeting.

The July invasion focused largely on Kerynia and Nicosia through the Pentadaktylos mountain range, with the clear aim to create a corridor from the north coast to the north of Nicosia, where there was a large Turkish Cypriot enclave. Nicosia was the responsibility of the Canadian Regiment at the time, whose priority quickly became to convince the Turkish Forces not to bomb the densely populated capital. Heavy fighting did ensue, which meant the Regiment faced significant challenges in trying to maintain the ceasefire along the Green Line.

Fighting took place all over the island between the Cypriot National Guard and the Turkish invasion Forces. UNFICYP often found that its ability to move freely around the island was challenged by the opposing forces. According to testimonies of the Finnish contingent operating in the Kerynia/Pentadaktylos District, the Swedish contingent in the Famagusta District and the Danish contingent in the Lefka District, the focus of UNFICYP quickly became to maintain its channels of communication with local communities, to prevent or halt outbreaks of intercommunal fighting, which by then had become increasingly heated as a result of the invasion and the clashes between the Turkish army and the National Guard. With the ultimate goal to prevent fighting between the two communities, either through negotiation or deployment of its forces, UNFICYP worked on halting sieges, releasing captured groups from either community by the other and preventing organised attacks, as well as working around the island to achieve local ceasefires between the communities. All against the backdrop, and because of, a conventional, full-scale war, with an attacking army multiple times stronger in capabilities and numbers than the National Guard, and an UNFICYP, that had neither the authority, nor the military means to engage.

A UN negotiated ceasefire started on 22 July, but outbreaks of violence continued, as the Turkish army was moving to expand its hold on the ground. The representatives of the two communities, Glafkos Clerides for the Greek Cypriot community and Rauf Denktash for the Turkish Cypriot community, and the foreign ministers of the three guarantor powers were due to meet in Geneva to negotiate an agreement for a settlement, that would end the fighting on the island. It was however clear, from UNFICYP records, that Turkey’s military objectives had not concluded in July. While the Geneva talks had not yet concluded, on 14 August Turkey launched its second invasion.

A larger offensive on the ground, by air and by sea, with the clear goal to expand the area it controlled east to Famagusta and Karpasia and west to Morphou and Lefka, with some of the most intense fighting of the war taking place in Nicosia. More than two hundred thousand Greek Cypriots were forced from their homes becoming refugees in their own country. In the UK today, that would be the equivalent of over 20 million people. Turkey expanded its 7% hold from the July invasion to the nearly 37% of the island it militarily occupies to this day.

The devastation was immense. It continues to this day for those who are still looking for loved ones, the missing people of Cyprus, and those who have lost their home, their livelihood. The hundreds of thousands of civilians in need of protection and humanitarian assistance quickly led to the expansion of UNFICYP’s mandate, with emergency assistance, and thereafter, humanitarian relief to the displaced becoming a major part of it. UNFICYP troops facilitated evacuations, of both locals and foreigners, food relief convoys and deliveries to small communities remaining in the north in the immediate aftermath of the invasion. UNFICYP guarded refugee camps in the months that followed and, for as long as it was able to operate in the north, it prevented looting and harassment of civilians.

In the face of war, UNFICYP protected civilians as a priority, which today is understood to be a core pillar of UN Peacekeeping. It was certainly indispensable to Cyprus in 1974 and the years that followed.

By 1975 the two communities had found an arrangement in the Third Vienna Agreement to allow for the movements of populations across the ceasefire line, with priority given to the re-unification of families. The Turkish Cypriots in the south would be allowed to proceed north with the assistance of UNFICYP. The Greek Cypriots in the north would be allowed to stay if they so wished and be given help to lead a normal life, including facilities for education and for the practice of their religion, receive medical care and have freedom of movement in the north. The remaining Greek Cypriots in the north wishing to move to the south would have been permitted to do so. Peacekeepers facilitating the implementation of people moving can attest to what extent civilians were actually permitted to exercise free will. It is estimated that 20 000 Greek Cypriots remained enclaved in the north. The number gradually diminished, with only 300 remaining today. Still, UNFICYP delivers books for the school, assistance for the elderly, and importantly, before the crossing points opened in 2003, UNFICYP delivered news between families on both sides of the divide. UNFICYP’s work has not been unimpeded and life for the enclaved Greek Cypriots has been anything but normal.

To this day, UNFICYP patrols and monitors the buffer zone separating the Turkish occupation forces and the Cyprus National Guard. In the absence of a formal ceasefire agreement, UNFICYP’s troops and police officers deal with hundreds of incidents each year. Only this summer the occupation security forces attempted to violate the status of the buffer zone by constructing a road from the occupied village of Arsos towards Pyla. This would have constituted a grievous violation of the status quo and the most serious violation of the buffer zone since 1974. On 18th August, UN peacekeepers in exercising their mandate, stood in the way of this attempted construction and as a result were assaulted and UN vehicles bulldozed, resulting in injury of several peacekeepers, including British peacekeepers.

UNFICYP’s goals today in addition to the original 186 mandate include the building of confidence between the two communities, in order to facilitate reaching a peaceful settlement. In doing so, eliminating threats and facilitating safer freedom of movement, the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) became an integral component of UNFICYP, to reduce the threat of landmines and explosive remnants of war. UNMAS also provides assistance to the Committee on Missing Persons, a bicommunal body with the participation of the UN, tasked with recovering, identifying and returning to families the remains of their loved ones. UNMAS ensures safe access to areas where the Committee on Missing Persons conducts its activities in.

In a world of geopolitical turmoil it may be convenient for some to look at Cyprus and say that there may not be peace but there is quiet. However, peace is not merely the absence of war, but the presence of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. This does not exist in Cyprus whilst there is still a continuing military occupation that separates the two communities. The ceasefire line that runs across the length of the island is a constant reminder that the situation cannot, in any way, be considered as normal. These are the basic facts.

UNFICYP’s presence continues to be indispensable. Maintaining the de facto ceasefire allows at least for space for the two communities to engage in a political process that we hope will lead to a negotiated settlement. A settlement on the internationally agreed UN framework of a bizonal bicommunal federation. The Security Council notes that the necessity of UNFICYP’s continuing presence on the island illustrates how the status quo is unsustainable. And it is true, the situation on the ground is not static. The Turkish army continues with its efforts to alter the military status quo, pushing forward its positions in a number of areas across the UN buffer zone, including in Strovilia, or moving their forces forward from the ceasefire line in Nicosia. In the last three months they moved forward in two locations, very close to civilian, inhabited neighbourhoods, posing a real and acutely felt threat to the security of the people in the area.

Earlier this week Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan in a public statement suggested that Turkey should have pushed further south in 1974, making Cyprus completely Turkish.

Let those words be understood. Our quest for peace in Cyprus can start with a settlement between the two communities. Peace however, needs more. The sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of our country continues to face a real, serious and persistent threat, which needs to be addressed.

The Cyprus Government has fully engaged with the UN Secretary General’s Personal Envoy, who assumed her duties at the beginning of this year. President Christodoulides reiterated the commitment of the Greek Cypriot side to the agreed UN framework for a solution to the Cyprus problem and the restarting of a substantial process of negotiations with the Turkish side. In the presence of the UK Government Minister, the Earl of Minto, I would like to recognise the support of the UK Government in the efforts to find a negotiated settlement on the basis of the agreed UN framework.

Many of the events I have included in my remarks come from the testimony of the Commander of the British contingent in UNFICYP in 1974, Brigadier Francis Henn, who also served as UNFICYP’s Chief of Staff. His book “A Business of Some Heat” is a valued historical record of what happened in Cyprus.

The sheer number of British veterans who served in UNFICYP illustrates the closeness of the relationship between Cyprus and the United Kingdom and the importance of the historical connection of our countries and peoples.

In closing it is appropriate to remember and pay tribute to those service men who lost their lives in Cyprus while wearing the blue beret. There have been 187 fatalities among the peacekeepers and UN staff serving in Cyprus and we honour their memory today.

In ending allow me to say to you the veterans seated before me, that I am truly humbled by your presence and your acceptance of our invitation to mark the 60 years of UNFICYP, but most of all, for your service. As the inscription on the memento of this event given to the veterans and spouses of veterans no longer with us says, thank you from a grateful nation.

I am honoured to have with us as well the Minister for Defence, the Earl of Minto, representing the Secretary of State for Defence, the Hon. Grant Shapps, and I would like to invite him to offer his remarks.